The Heat and Buildings Strategy – building the future or hot air?

As winter blows in this week, many people will be turning up their central heating and huddling around fireplaces. The recent Storm Arwen served as a timely reminder of the need for robust energy distribution systems, with almost 1 million homes affected and three people killed.[1] At the same time as keeping us warm, there is also urgent need to curb carbon emissions produced by home heating, which in 2019 made up a huge 18% of total emissions.[2]

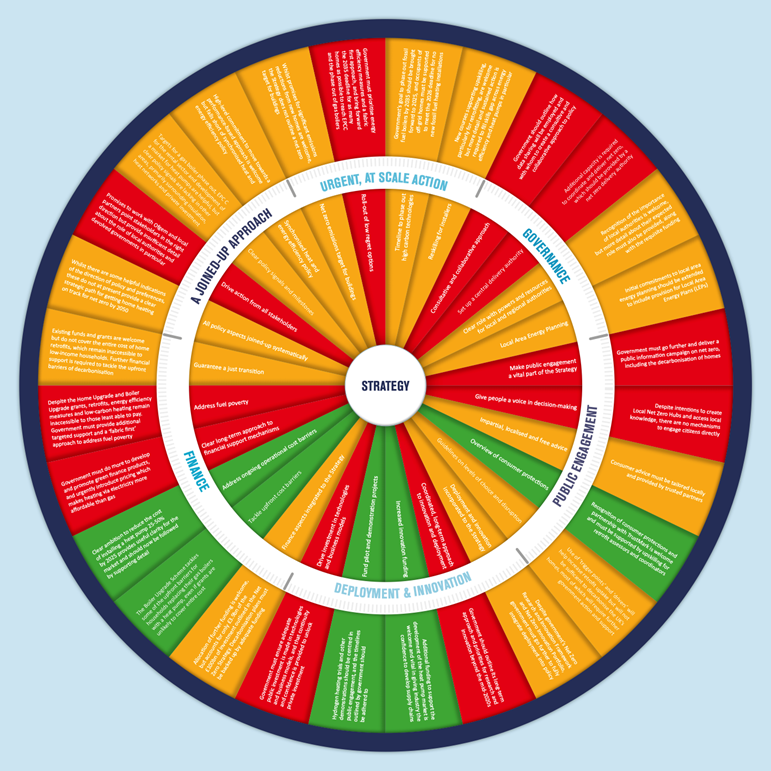

In Pipeline to 2050, we set out strategic tests for government’s long-awaited Heat and Buildings Strategy and priorities for urgent action. Measuring the Strategy against our tests, the picture is mixed. Crucial areas need much more policy detail and funding, whilst in others, good intentions must be followed by delivery. Nonetheless, positive action is promised in several areas, including addressing upfront barriers to low-carbon technology, demonstration projects and increased innovation funding.

Urgent, at scale action

Whilst the Strategy contains high-level recognition of the importance of a ‘fabric-first approach’, it lacks necessary detail on energy efficiency measures and falls far short of providing the support people will need to insulate their homes. Regarding the phaseout of fossil fuel boilers, 2035 is not ambitious enough to achieve the carbon reductions the UK needs. And we can go much faster - a gas boiler is typically replaced every 14 years, with 1.7 million changed in 2019, so by 2035 the majority of these 1.7m need to be low carbon alternatives.

Governance and capacity

Net zero will need a huge amount of coordinated effort, yet the Strategy doesn’t propose any new capacity for co-ordinating the transition, as our recent report Connecting the Watts recommends. There is positive recognition of the importance and role of local authorities, with the Home Upgrade Grant in place as the long-term successor to the Local Authority Delivery Scheme (LAD). However, this Scheme remains underfunded by £1.4bn against Manifesto commitments, and local authorities will need more detail, funding and capacity to even begin thinking about net zero.[3]

Public engagement

Despite describing it as “a vital element of successful decarbonisation”, plans for meaningful public engagement are missing from the Strategy. In particular, despite intentions to create Local Net Zero Hubs to access local knowledge, there are no mechanisms to engage people directly, whether via participatory assemblies or public information campaigns.

New consumer protections are a positive step towards engagement, with promises for a Code of Practice and Consumer Charter, and an extension of the quality assurance scheme TrustMark as we recommended in Connecting the Watts.[4] Recognition of ‘trigger points’ and ‘drivers’ in behaviour change is also important to increase uptake of retrofitting and low-carbon technology, but won’t be enough to decarbonise all the UK’s homes. Meanwhile, BEIS found that only 36% of people know a lot or a fair amount about home heating’s contribution to climate change, which only makes clear, widespread public information and engagement more urgent.[5]

Deployment & innovation

Planned demonstrations are both timely and useful, including a neighbourhood trial for 100% hydrogen heating by 2023 and a village scale trial by 2025, before strategic decisions on its role are made by 2026. Government should make the most of these demonstrations by centring them in public engagement campaigns as real-life examples of what the transition could look like. A £60m investment in the Net Zero Innovation Portfolio ‘Heat Pump Ready’ programme to develop the heat pump market is also a welcome step.

Worrying gaps remain around funding and long-term research and innovation, with no research programmes indicated to extend beyond the mid 2020s and overreliance on the potential of private investment. Rather, government must ensure adequate public investment is made in technologies and business models, as well as providing policy and regulatory continuity and confidence to unlock private investment.

Finance

The Boiler Upgrade Scheme grants offer up to £6,000 to households replacing their gas boiler with a heat pump, which tackles some of the upfront barriers for consumers. But with these grants unable to cover the entire cost of a heat pump, or contribute to home insulation, those least able to pay and most in need of home energy improvements are left without access to any support. To address fuel poverty, government needs to provide additional targeted support and approve improved minimum energy efficiency standards across private rental and social housing, as the Committee on Fuel Poverty suggests.[6]

A joined-up approach?

The Heat and Buildings Strategy contains plenty of good intentions and indications of positive direction. The Boiler Upgrade Grant, new skills and standards and plans for the heat pump market are highlights of this Strategy. Overall, however, there is disconnect between the positive direction and the absence of action plans, as well as significant holes in important areas like energy efficiency. To translate intention in action, this Strategy must now be followed by funded delivery-focussed policies.

[1] BEIS, Update on Storm Arwen (2021).

[2] Climate Change Committee, 2021 Report to Parliament: Progress in reducing emissions (2021), p. 111.

[3] EEIG, Still waiting for the green light (2021), p. 2; Policy Connect, Connecting the Watts: The case for a net zero delivery authority (2021), p. 18.

[4] Policy Connect, Connecting the Watts: The case for a net zero delivery authority (2021), p. 25.

[5] BEIS, Public Attitudes Tracker: Heat and Energy in the Home Autumn 2021, UK (2021), p. 1.

[6] Committee on Fuel Poverty, Annual Report (2021), pp. 6-7.